Helping Children with Anxiety and Trauma: Bottom-Up Approaches for Parents

Recently I have gotten to know many families impacted by anxiety. Children who dread separation from their parents at the carpool line, teenagers who can’t imagine walking into a cafeteria and trying to find a place to sit, and parents wanting more than anything to give their child relief from these symptoms. As I have walked alongside these families, I have noticed an overlap in my treatment of a child who has experienced trauma and a child who is experiencing anxiety.

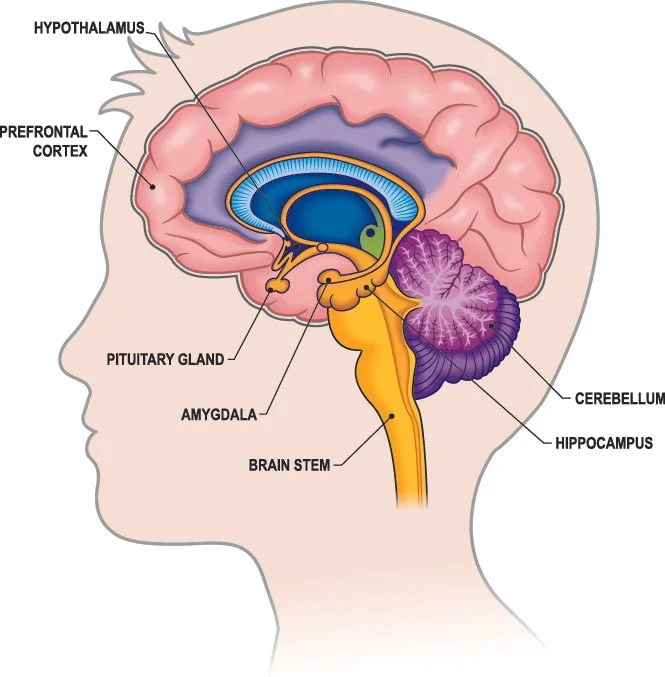

A Brief Brain Lesson on Trauma and Anxiety

When thinking about trauma and anxiety, it can be helpful to learn a little about our brains. There is a part of the brain called the amygdala, and its primary job is to scan for threats and send signals to our nervous system if a threat is perceived. Sometimes it perceives a threat correctly, and our body responds by protecting itself through fighting the threat or fleeing the threat. Other times, it may send a signal when there is not actually a threat. Trauma and anxiety are similar in that both involve the activation of the threat signal, and this signal then activates the fight-or-flight stress response.

The amygdala is in the bottom part of the brain, or as some people refer to it, the downstairs brain. The downstairs brain helps with basic functioning such as breathing, blinking, or moving as well as impulses and big emotions like fear or anger. This bottom part of the brain develops early. The top part of the brain, or the upstairs brain, is responsible for critical thinking, creativity, decision making, and nuance. This upstairs brain is not fully developed until a person’s mid-twenties! Other terms coined for the upstairs/downstairs brain include rational/emotional brain, thinking fast/thinking slow brain, conscious/unconscious brain.

How Understanding the Brain Helps with Childhood Anxiety

When a person feels safe, they have easy access to that upstairs brain. Both levels of the brain communicate and send information back and forth. Individuals are able to think logically, express emotions, make informed decisions, problem solve, and come up with creative solutions. The brain is functioning out of this secure base of “safety.” However, when a threat is perceived–whether real or imagined–it is much more difficult to access that upstairs part of the brain. This can lead to responding emotionally (usually with fear and anger), acting impulsively, and/or feeling stuck in a state of hyperarousal (feeling on guard and scanning for threat).

Because children’s upstairs brains are still developing, it is already more difficult for them to problem solve, empathize, and think logically. If this is compounded with trauma, fear, or anxiety, it can feel impossible for a child to regulate and come out of a fight-or-flight response. Staying in this state of hyperarousal can become physically and emotionally exhausting. It is a state bodies are not meant to stay in, which is why the body will often protect us by switching into dissociation mode. Dissociation is a coping mechanism for overwhelming stress or trauma that can be helpful, as it provides a way to temporarily escape and “shut off” the mind. While helpful, and even necessary, for survival at times, using dissociation to cope long-term can make it difficult to stay in the present moment, and connection to the body is not possible when practicing dissociation.

Bottom-Up Approaches for Anxiety and Trauma

Both anxiety and trauma elicit the same type of survival response, which not only limits one’s access to the upstairs part of their brain, but also creates physiological responses of unsafety in the body. Because of this, using “bottom-up” approaches to address anxiety and fear can oftentimes be a more effective approach. Bottom-up approaches are often also referred to as physical or somatic coping skills. These skills focus on connection to the body and restoring a sense of safety in the body. Somatic skills speak directly to our body, which is crucial as access to the top part of our brain is shut off when a threat is perceived. Once feelings of safety are established, strategies using the upstairs brain such as rationalizing, reframing, or addressing thought patterns, can then be implemented.

Especially when walking alongside a child in a moment of crippling anxiety, it can be helpful to remember this approach. The desire to rationalize or use logic with a child in moments of irrational fear can feel like second nature. For example, it’s time for school drop off, and your child is refusing to get out of the car. It’s natural to want to reason with your child by saying something like, “Honey, we have done this 100 times before–you know there is nothing to be afraid of.” If, however, we could shift our thinking and first help our child reach a place of safety and connection with their body, they would then be able to access the top part of their brain and join the parent in more rational thinking and creative problem solving. Consider something like, “I hear you are afraid of going to school today. Let’s do our 5-4-3-2-1 scavenger hunt, and then we can talk more about it.”

Somatic Strategies for Children with Anxiety

Here are some bottom-up approaches to try with your child. It can be helpful to try these strategies when a child is in a neutral state of mind and their stress response is not activated. The more they practice when both parts of their brain are talking to each other, the easier it will be to use these skills when access to their upstairs brain is limited.

Grounding Somatic Scavenger Hunt

Have your child name 5 things they see, 4 things they feel, three 3 they hear, 2 things they smell, and 1 thing they taste. This is especially fun to do outside. If you find your child is hesitant to go through each of the senses, start with smaller questions such as, “How many light fixtures do you see around you right now?” “How many different bird songs do you hear right now?”, “Can you tell where your shirt is hitting your body right now? Does it feel loose or tight?”, “How does the chair feel on your back? I wonder if we can create that same feeling with your feet on the floor.”

Create Cold for Stress Regulation

Having short-term contact with very cold temperatures can help slow our heart rate which slows down our body’s natural stress response. Washing your hands with very cold water, squeezing ice cubes in your hand, placing an ice pack on the side of your neck for 5 minutes, or splashing cold water on your face are all quick ways to regulate the body

Dragon Hugs / Butterfly Hugs

Have your child cross their arms over their chest like they are giving themselves a hug. While they hug themselves, have them alternate tapping their right and left hands. While they do this, have them take deep breaths. This alternating tapping of shoulders or chest is working both sides of the brain and helps to regulate the nervous system and reduce the body’s stress response.

Parents Are Crucial in Helping Children with Anxiety

Children often look to their parents for co-regulation. Do not be afraid to get on the floor with your child and participate in the tapping or dragon hugs. The more your child experiences this co-regulation, the more they will begin to use these strategies themselves and feel empowered by their ability to calm their bodies.

Parenting a child with anxiety can feel overwhelming and can leave you feeling powerless and discouraged. As parents, you play a vital role in both modeling and supporting your child’s progress in learning to regulate their own nervous systems. It takes time, patience, and practice, but progress always begins with a first step. So, if you are parenting a child who is experiencing anxiety, try practicing one of the bottom-up strategies. You may even find yourself experiencing greater regulation with them. As always, we at Dwell are here to walk with you in the journey.

Author: Mollie Pinkham, LCSW

To learn more about therapy for kids, teens, and parents, visit our Child & Teen page or reach out to info@dwellministry.org for more information. To book a session with Mollie today, click on the link below or email her directly at mollie@dwellministry.org.